Three Tax Bucket Strategy for Financial Independence

Right away, I want to clarify something before you dig too deep into this post.

There are two different “three bucket” strategies that are often referred to as it relates to finances.

In one, the three-bucket strategy is a reference to three ranges of time where you’ll need access to funds you’ve saved or invested. The three ranges are short-term (0-2 years), intermediate (2-5 years), and long-term (5+ years).

This post is not about that three-bucket strategy.

Instead, we’ll be referring to three different types of tax treatment for your savings and investments; the three types being Taxable, After-Tax, and Tax-Deferred.

There is also an occasional bit of confusion that arises out of what exactly each of these three monikers is describing specifically. Let’s attempt to clarify that now as well.

The Taxable Bucket contains money or investments that have already been taxed (usually as income) and any future gains, dividends, or appreciation will be subject to tax (usually as either a dividend, capital gains, interest, or income). Most often, when I refer to a “taxable” bucket, I’m speaking of a taxable brokerage account.

The After-Tax Bucket refers to money or assets that have already been taxed and any future earnings or growth are completely tax-free. The most common account you’ll find in the after-tax bucket is a Roth account. In fact, many just call this bucket the “Roth Bucket” because it’s a more direct path to identification. I’m having a bit of trouble coming up with another example that won’t require another lengthy clarification, so we’ll just leave it at Roth’s.

The Tax-Deferred Bucket is sometimes also known as the “Pre-Tax” bucket though, out of my abundant love for consistency, I will try to stick with the former description. There are several examples of tax-deferred accounts. The most common is a traditional IRA or 401(k). Dollars in a health savings account that aren’t used for a qualified medical expense would also be considered tax deferred.

Now that we’re all clear on what we’ll be discussing, let’s talk about why the three-bucket strategy is important.

Tax Flexibility

Options are nice to have.

Think about your shoes for a minute. Like most people, you probably have more than one pair of shoes.

In my closet, there are dressy shoes, running shoes, boots, flip-flops, slippers, and many more.

Each pair I own has some unique features that make them suitable for a particular purpose.

For example, my boots are waterproof which makes them great for a rainy day, but not ideal for a hike through an arid desert.

I also have a pair of trail running shoes that were great on a trip we took to Moab, Utah, but they may draw a rebuke if I wore them in a business meeting where I work.

I could wear flip-flops in a snowstorm but if I had another option, why would I?

Likewise, there are three basic account options for investing, each with its own tax plusses and minuses.

And, like shoes, having optionality on how you save, earn, and distribute using these accounts can provide you with exceptional flexibility in how and when you are taxed.

In other words, multiple buckets give you maximum control over taxes, at least as much as the law allows anyway.

Let’s take a deeper look at each bucket to see how.

The Taxable Bucket

Tax Treatment:

- Funded with money that has already been taxed.

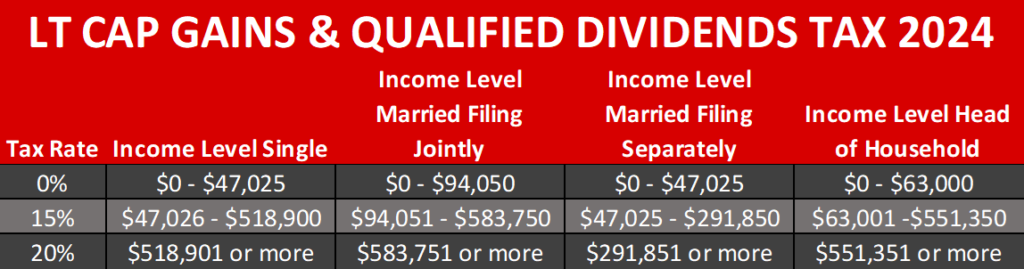

- Long-term gains and qualified dividends taxed at 0%, 15%, or 20%.

- All other earnings are subject to income tax.

Primary Uses:.

- Long-term capital gains and qualified dividends taxed lower than income.

- Great source of funding for taxes associated with Roth conversions.

- Excellent way to make donations to charity or leave an inheritance.

We’ll start with the least beneficial of the three buckets, the taxable bucket.

The taxable bucket is filled with assets that have already been taxed to some degree (except maybe in the case of an inheritance). Most often, they come from your taxable income that’s directed toward saving and investing or they’re extra dollars you have leftover from the sale of an appreciated asset.

Either way, the cash you put into a taxable account is left over after Uncle Sam has claimed his share.

Furthermore, any earnings, dividends, capital gains, interest, etc. that these contributions earn are eventually subject to tax as well.

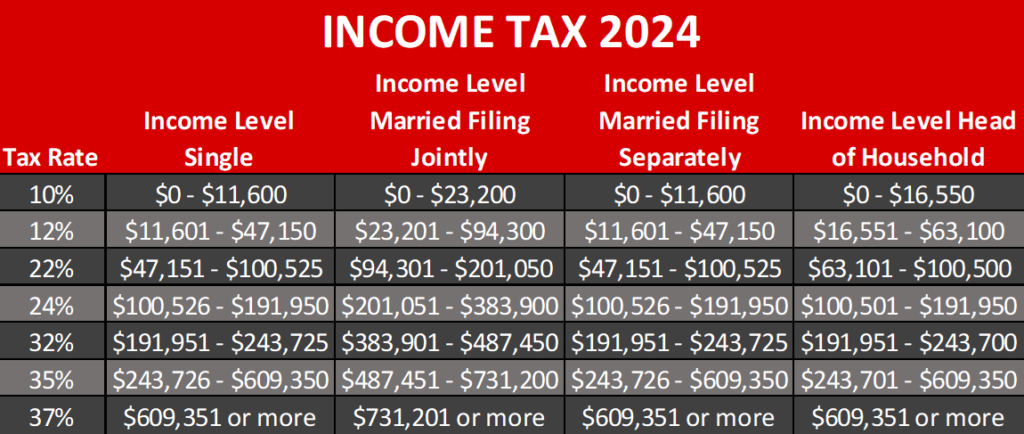

Long-term capital gains (for assets owned over one year) and qualified dividends are taxed at 0%, 15%, and 20% depending on your adjusted gross income.

Short-term capital gains, non-qualified dividends, bond coupon payments, interest income, etc. are all taxed as income, so there’s no real tax advantage when these assets generate those types of earnings.

Naturally, you’ll want to own securities that either don’t generate dividend income or, if they do, produce qualified dividend income. You’ll want to hold those securities in your After-Tax or Tax-Deferred space.

Look for tax-efficient investments like mutual funds or ETFs that are designed to generate little or no taxable earnings for your taxable accounts.

So why would you want to own any investments in a taxable account?

The first, and most obvious reason, is that you want your money to grow.

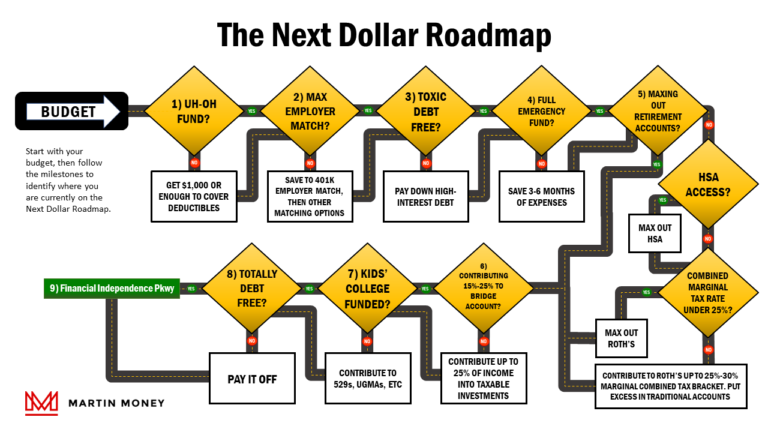

With that aside, it’s not tax-optimal to fund a taxable account until you’ve either met your savings goal using after-tax or tax-deferred spaces or maxed them out entirely. There is, however, a case for making contributions if you have liquidity goals (more on that later).

Assuming though, that you have indeed fulfilled your funding foals for after-tax or tax-deferred investing, then using a taxable account makes perfect sense.

That’s because using assets in a taxable account to generate long-term capital gains and qualified dividend income will provide you with investment earnings that are taxed at far lower rates than normal income, interest, or other investments.

Here are a couple of tables illustrating the tax rates for various levels of income.

As you can see, you could save anywhere from 7% to 20% depending on your adjusted gross income by investing in assets that produce long-term gains and qualified dividend income.

Taxable accounts also provide a handy way to fund Roth conversions as you approach the age of required minimum distributions.

I won’t go into a lengthy explanation, but Roth conversions are a way to move money out of a tax-deferred account and into an after-tax account in a strategically lower income tax year.

Since Roth conversions are a taxable event, you’ll owe income taxes on any amounts you convert. If you don’t have cash available in a taxable space, you’ll have to use tax-deferred or after-tax resources to fund the conversion.

This isn’t very efficient because it’s a financial cannibalization of assets that were protected from taxes to protect other assets from taxes. You’d rather use money with no significant tax advantage to pay for conversions.

Another potential benefit of taxable accounts is the tax efficiency they can provide to givers.

Once again, instead of chasing another rabbit, I’ll simply say that donating equities may allow you to obtain a free step-up in the cost basis while making no material changes to your portfolio. You can read more about the nuts and bolts of that process by reading this post about donating stock.

Finally, leaving assets in a taxable account for your heirs is also a great way to leave tax-free inheritance to them after you kick the bucket.

The Tax-Deferred Bucket

Tax Treatment:

- Funded with tax-deductible contributions.

- Earnings grow tax-deferred.

- Withdrawals are subject to income tax.

Primary Uses:

- Tax-advantaged investment growth.

- Qualified Charitable Distributions.

- Reduce income tax exposure in years with high adjusted gross income.

Tax-deferred accounts as we know them today made their appearance in the late 1970s, though it would take a few years before they were widely used.

Up until 1998, when Roth IRAs were introduced, tax-deferred investing was by far the most widely used tax-advantaged method to save for retirement.

If one fails to account for the benefits of tax-deferred earnings growth, you might wonder what difference it makes if everything you withdraw from the account is subject to tax.

As an example, suppose you contribute $5,000 a year to a 401(k) for 40 years. For simplicity, let’s also assume you’re in the 22% tax bracket for the entire 40 years and when all withdrawals are made.

If you received an average rate of return of 8% over the course of this period, your account would have $1,398,905 when you reach retirement.

Once you make withdrawals and subject this balance to a 22% income tax, you’ll have $1,091,146 remaining.

However, if you made the same contributions to a taxable brokerage account, receiving the same 8% return, subject to just a 15% long-term capital gains tax, you’d only have $927,474 to show for the same invested amount.

That’s a net of $163,672 more just by using a tax-deferred account to invest instead of a taxable account that doesn’t receive any of the tax benefits.

The difference is the result of being able to invest dollars that haven’t been taxed and earning returns from those dollars which will only partially be taxed later.

Eventually, you will owe taxes but tax-deferred accounts provide yet another opportunity to potentially lessen your tax burden.

When you make a contribution to a tax-deferred account, you basically enter into an agreement with the government that you’ll save for retirement if they agree to leave you alone to do that for a long, long time; but not indefinitely.

It’s like they say, there is certainty in death and taxes.

When you reach age 73 or 75, depending on when you were born, you will be required to make taxable distributions (known as required minimum distributions or RMDs) from your tax-deferred accounts.

There are a few ways to reduce or limit the taxable impact of RMDs which you can read about here or watch here.

A very popular way to reduce RMDs is to make Qualified Charitable Distributions or QCDs directly from an IRA (you can roll other tax-deferred accounts into an IRA without any tax obligations).

Another very popular way to reduce RMDs is to make Roth conversions in low-income tax years between retirement and RMD age, so less of your investment portfolio is subject to RMDs when the time comes.

We touched on this already and will again below, but having the conversion strategy available is a huge benefit that facilitates the option of paying taxes on your tax-deferred assets when you want to, not when you have to.

And that’s just a small part of the last benefit of tax-deferred accounts we’ll discuss.

Tax-deferred investments provide a tax arbitrage opportunity in years where you have a high taxable income.

If you have a high income, then you can reduce your income tax exposure by directing money into a tax-deferred account since each contribution is tax-deductible (to an extent).

If you are in a lower tax bracket in retirement, then you can make withdrawals when your marginal tax rate is lower, sparing some of your hard-earned money from taxes.

For example, if you make contributions when your marginal tax rate is 34%, but make withdrawals when you are in the 12% bracket, you’d save 22 cents on every dollar you put into tax-deferred accounts.

The After-Tax Bucket

Tax Treatment:

- Contributions are not tax-deductible.

- All earnings and withdrawals are completely tax-free.

Primary Uses:

- Tax-advantaged investment growth.

- Pay taxes for investments in years with low adjusted gross income.

- Remove tax risk permanently.

Central to the theme of this post is the concept that using a diverse group of accounts, with a variety of tax treatments, will lead to better financial outcomes in the long term.

With that said, if there’s a “best bucket”, the after-tax bucket is it. I’ll stop short of saying you want all of your money in an after-tax account, which I’ll explain below, but you do want just about all of your money in an after-tax space.

The after-tax bucket is the only space that is completely yours. Uncle Sam has taken his piece of the pie and left you to enjoy the remainder at your pleasure.

In all other cases, the government is your silent partner. They may not meddle in the day-to-day affairs of your investing business, but when the time comes to reap the harvest of your efforts, rest assured, they will be there with hands outstretched (palms up of course).

Not so with an after-tax account.

Aside from the emotional benefit of just knowing it’s all yours, after-tax accounts provide the same benefits of uninterrupted earnings growth, you’ll just start with less because you have to pay tax before you make a contribution.

This brings me to an important financial principle: If your tax rate, term, and rate of return are all equal, the post-tax totals in your tax-deferred or after-tax accounts will be the same.

As a quick, simple example, let’s assume you are in the 10% tax bracket, you want to put $5,000 into an IRA, and you expect it to return 8% this year.

If you invest tax-deferred, you’ll contribute $5,000, earn $400, and then pay $540 in taxes upon withdrawal for a final value of $4,860.

If you go the after-tax route, you’ll pay $500 in taxes, contribute the remaining $4,500, and then earn $360 for a final value of $4,860.

Like I said, the same.

This shows that even though there is value in cutting the government out of your future earnings, it doesn’t cost you anything extra if all other conditions remain the same.

That’s less risk for the same reward. A definite bonus for after-tax investing.

Of course, that’s only if conditions are equal over extended periods and we all know that the likelihood of tax brackets remaining the same and our ability to stay in them is pretty low.

I wish I had a crystal ball to share that would help us all identify the optimal tax-advantaged investing strategy. In lieu of that, we’ll just have to settle for this rule of thumb:

If your combined state and federal marginal income tax rate is below 25%, you will likely come out better in the long run if you purchase investments through an after-tax or Roth account.

If your combined state and federal marginal income tax rate is above 30%, tax-deferred investing is more likely to pay off.

If you’re in the 25% to 30% range, then it’s a bit less clear. Personally, I do a little of both with a slight tilt toward Roth, but you should follow your own personal preference.

Why Not All Roth?

Now, I mentioned previously that you shouldn’t necessarily try to get all of your money into the after-tax bucket.

It would be perfectly natural to wonder why. After all, what’s not to love about tax-free investing?

Let me provide a couple of examples to illustrate why you may not want to move everything to Roth.

First, if you make regular donations to a qualified charity and plan to continue doing so, it wouldn’t make much sense to pay tax on contributions to an after-tax account and then make a donation out of that account only to get those tax dollars back through a deduction taken at a later date.

In a way, that’s like loaning the money to the IRS until you reclaim it after a gift.

Instead, do your best to forecast donations to charities and leave something in tax-deferred or taxable accounts to make gifts from.

Another reason is estate planning. After-tax accounts, like Roths, can be bequeathed to heirs without any tax liability in addition to possibly providing an additional ten years of tax-free earnings.

Tax-deferred accounts, on the other hand, are taxable as income to beneficiaries as they remove money from the inherited accounts.

This makes Roth accounts a very attractive way to receive an inheritance.

But what if you’re in a higher tax bracket than the beneficiaries of your estate? You wouldn’t want to pay tax at your high income tax bracket so they can avoid paying taxes from their lower brackets after they receive the inheritance, would you?

But that’s exactly what would happen if you converted your tax-deferred dollars to a Roth before leaving the remainder as an inheritance.

Beyond the circumstances we’ve covered (high income tax bracket, inheritance considerations, and giving strategies) there’s not a more tax-efficient place to invest than in an after-tax account.

Wrap Up

I know that was a lot of information, but hopefully, it helps you to see many of the ways a three-bucket investing strategy can provide a significant tax payoff.

To understand more about how to use this strategy effectively, I recommend a couple of things.

First, taxes are one of the least interesting things mankind has ever conceived, but you should strive to understand how they work. The better you grasp your own tax situation, the higher your likelihood of using the three buckets effectively.

Finally, check out similar posts at MartinMoney.com or on our YouTube channel.